The Evidence from Arabia for Lehi’s Trail in the Book of Mormon: Updates

In two articles at Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-say Saint Faith and Scholarship, I tackle a long series of criticisms of the most interesting evidence related to the Book of Mormon from the Arabian Peninsula. The articles are “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Map: Part 1 of 2” and “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Map: Part 2 of 2,” both from 2016. Here I follow up on that publication with updates, revisions, and additional issues that were not fully addressed there.

First, here is a photo kindly provided by George Potter with my added caption showing the leading candidate for the River Laman and the Valley of Lemuel at Wadi Tayyib al-Ism, about 75 miles south of the northern tip of the Red Sea, or about a three-day journey by camel.

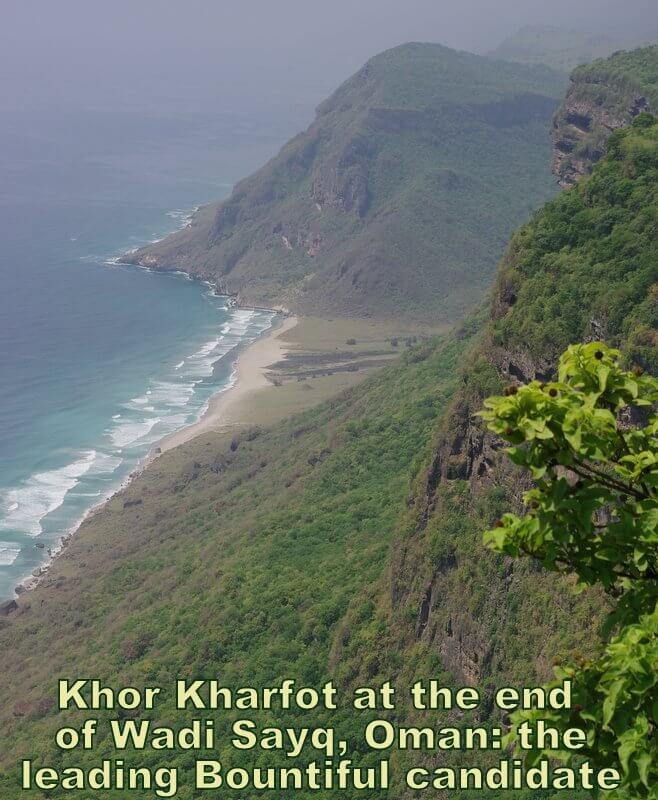

Here is a photo that was included, kindly provided by Warren Aston, showing a view of Khor Kharfot, which I consider to be the leading candidate for Bountiful, on the east coast of the Arabian Peninsula in Oman.

Overview

Critics of the Book of Mormon have finally made a serious, detailed response to the large body of evidence for the Book of Mormon from the Arabian Peninsula. A good deal of this evidence has been featured at sources like the Maxwell Institute, Meridian Magazine, and FAIRMormon, revealing such finds as the discovery of a remarkable candidate for the place Bountiful meeting 12 key criteria from the Book of Mormon and recent archaeological confirmation that the rare NHM name existed before (and after) Lehi’s day in the right vicinity for Nahom. The growing body of evidence also includes an excellent candidate for the River Laman and Valley Lemuel and the place Shazer. Until now, few critics have seriously considered the evidence, instead generally nitpicking at details and insisting that the evidences are insignificant. Recently more meaningful responses have been offered at Patheos.com by two well educated writers showing familiarity with the Arabian evidences and the Book of Mormon. One comes from a history professor, Philip Jenkins, and the other from an anonymous Mormon, “RT,” with a divinity degree from Harvard. [2] The two make a large number of seemingly damaging criticisms that I felt demanded a detailed response. Their attack goes far beyond what other critics have done, drilling down into the details of the Old World setting of the Book of Mormon often with sophisticated and extensive arguments to allege that it Nephi’s account is implausible, not historical, and easily explained by sources Joseph could have accessed. Because I feel their work represents some of the best that our critics have been able to launch against the strongest evidence for Book of Mormon plausibility, it demands a detailed and thorough response, which is what I have attempted to provide in a two-part series that will appear in the Interpreter (mormoninterpreter.com) on April 1 and April 8 with the title, “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Map.” In spite of the light-hearted title, the topic is serious and involves over 100 pages and over 350 footnotes, intended to be a useful reference for future readers. In addition, ongoing updates to the information provided and answers to other questions not covered in the two articles will be available here (see also my “Book of Mormon Evidences” pages). The article has four sections split across two parts. Section 1 is an overview of the attacks, exploring over 40 points that are levied against Lehi’s Trail, with brief responses to each. Some of these criticisms are interesting, thoughtful, and occasionally creative. They include arguments against the role of sacrifices in the Book of Mormon, the lack of information about others encountered, the implausibility of using camels (generally required for the distances to line up with the leading candidates for places like the River Laman and Shazer), objections to the apparent word play on Nahom, and many more. For each of these objections, I feel there are reasonable responses and often important information that has been overlooked. In many cases, the answers are already available in the best works on Lehi’s trail, such as Warren P. Aston’s magnificent new book, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia and the related DVD, Lehi in Arabia. Section 2, also in Part 1, then reviews the state of our knowledge about Lehi’s Trail, including such highlights as the suitability of Wadi Tayyib al-Ism as a candidate for the Valley of Lemuel and the River Laman, the many evidences related to Bountiful, and the ability to reach it by following Nephi’s directions and actually going “nearly eastward” from Nahom. Through ever better maps, exploration, archaeological work, and other scholarly investigation, our knowledge of the Arabian Peninsula has grown dramatically from Joseph’s day. Through all of this, not one detail in the account of Lehi’s Trail has been invalidated, though questions remain and much further work needs to be done. Importantly, aspects that were long ridiculed have become evidences for the Book of Mormon. There is a trend here that demands respect, and no mere map from Joseph’s day or even ours can account for this. What Joseph theoretically could have achieved with the best maps in his day is the topic of Section 3, to be published in Part 2. There we review the details available on 11 leading high-end maps that include something related to Nahom (Nehem or Nehhm). We find that these high-end, European, and generally not widely accessible maps would have offered little assistance for a young or even experienced fabricator. While they could provide inspiration for a name mentioned once in the Book of Mormon, and could have informed Joseph of the general location of the Red Sea and Arabia, the theory that Joseph used such a map raises far more questions than it answers. For example, if he had a map, why was almost nothing on it used except an obscure name like Nehem that would mean nothing to his readers? If he used a map, why did he ignore the information they give and put Bountiful on the east coast? What could possibly have told him Bountiful would be nearly due east of Nahom? And how could he have guessed the existence of the River Laman or the hunting area near Shazer? In Section 3 we also consider the availability of such maps, including the creative theory that the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 could have created an information-rich environment for Joseph that would have made it easy to access abundant data for his Book of Mormon project. Could Joseph have obtained detailed information to support his drafting of 1 Nephi by surfing the “Erie Information Supercanal”? That romantic notion doesn’t withstand analysis. Further, if Joseph was relying on the information that he might find in libraries, bookstores, and cargo loads of information floating down the Supercanal, why did he leave his Bountiful-like oasis of information in 1827 and go into exile to a data desert, the virtual Empty Quarter of information in Harmony Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania (not the current Harmony near Pittsburgh), which didn’t even have a library and was far from the “Supercanal” and Joseph’s potential information networks? Joseph’s behavior shows that he apparently did not feel a need to be near bookstores, libraries, and his fellow farmer literati to search through documents every verse or so to come up with tidbits like the name Nahom for the purpose of adding evidence that would never be exploited and local color that no one else in his century would ever notice. Section 4 in Part 2 considers an important argument that may catch some readers by surprise. RT argues that it is “well known” and the result of broad consensus that the Exodus account, which Nephi is obviously familiar with and incorporates in his own description of their exodus, is mere fiction, a tale that wasn’t broadly known among the Jews until after the Exile. This claim derives from modern bible scholars who have dissected the text in efforts to explain its diverse origins. The “Documentary Hypothesis,” one of the leading theories used to explain origins of the Bible based on several hypothetical source documents, is a problem for Lehi’s Trail only if we accept a late post-exilic date for the Exodus-related sources. However, significant scholars such as Richard Elliot Friedman, find strong reasons for assigning earlier dates to the priestly material said to be a source for much of Exodus, and finds reasons to accept that some kind of historical Exodus from Egypt occurred. Indeed, there are significant reasons to question the claimed but illusory consensus about the non-historical nature of the Exodus, and to recognize that it is plausible for that record to have been on sacred written records in Nephi’s day. We will explore some of these reasons and find that rejecting the evidence in Arabia for Lehi’s Trail on the basis of the alleged lack of evidence from Egypt for the Exodus is an ironic and unfortunate application of biblical scholarship. If anything, what we learn from Arabia and the Book of Mormon may now be able to help us temper some of the claims being made by radical revisionists in biblical studies, the “minimalists,” who seek to discard much of the Bible as non-historical pious fiction. Nephi’s record, buttressed with hard evidence from Arabia, may be just the thing the scholarly world needs right now. From the absence of evidence for any map he could access to the details of the scribal process and its setting during the translation to the behavior of Joseph and his peers after the Book was published, everything about Lehi’s Trail in the Book of Mormon contradicts theories of fabrication by Joseph using maps and books of his day. The theories of fabrication fail to account for the text of the Book of Mormon. They fail to account for the evidences from the Arabian Peninsula. They fail to account for Joseph’s behavior during and after translation, such as moving far away from the Erie Canal to carry out the work of translation, and the lack of any effort to exploit the built-in evidence. Fabrication using a map simply makes no sense. How? With what? And especially, for what purpose? Jenkins’ “local color” theory makes no sense. The inability of even a modern Dream Map to explain the crown jewels of the Arabian evidence for Book of Mormon plausibility is well illustrated by one of the most interesting and counterintuitive aspects of Bountiful: its apparently pristine, uninhabited state when Nephi arrived. Remarkably, after having studied the best maps of Arabia and reviewed extensive information about Arabia, with the world’s treasures of knowledge at his fingertips as he prepared his heavily footnoted critique of Lehi’s Trail, our very educated and very modern RT concludes that it would “simply be impossible” for a place like Bountiful to be uninhabited.[3] That argument was fairly reasonable once, until the day a weary Warren Aston and his 14-year-old daughter stepped off a boat to explore a secluded area that didn’t look at all promising from the sea, only to discover what careful work would confirm is a remarkable and still uninhabited candidate for Bountiful.[4] That’s one of many important details in our crown jewels from Arabia that even well trained modern scholars with a world of maps can’t quite figure out. If understanding Bountiful is beyond their abilities, it certainly wasn’t possible for Joseph to come up with that, no matter how many books and maps he downloaded from the Erie Information Supercanal. Our modern critics also miss the significance of the eastward turn that so beautifully and plausibly links Nahom and Bountiful. And there are many more details from the evidence that simply cannot be explained from maps in Joseph’s day. Plucking Nehem off a map doesn’t explain the mystery of Nahom in the “right place” — meaning a Nahom where you can physically turn east and survive, a Nahom where you can find a verdant Bountiful nearly due east on the coast, a Nahom that is associated with ancient burial places, and a Nahom with a name linked to an ancient tribe that was obviously present in Lehi’s day, courtesy of archaeological evidence. Those details aren’t on any map that Joseph could have seen, unless it’s in somebody’s dreams. I must emphasize that the Arabian evidence, useful as it is, must not be understood as “proving” the Book of Mormon to be true. In the Gospel plan, faith is essential, so we understand that evidence should generally play a secondary role such helping individuals facing intellectual obstacles to have the courage and hope needed to move forward in faith. Sometimes, however, the evidence, mercifully, can do more than just help a traveler step over a nasty new barrier on the path. Sometimes the evidence is a gift box laden with nutrition and sweet delights for those willing to open it and taste. The evidence from Arabia is such a gift, in my opinion, and must not be minimalized, in spite of secular imperatives to do so at all costs. It is a case where there are mighty strengths in the Book of Mormon that demand to be considered and applied. So far, detailed, lengthy, and creative efforts to turn those strengths back into weakness have failed. [1] Exemplary sources include the following books: Warren P. Aston and Michaela K. Aston, In the Footsteps of Lehi (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book Comp., 1994); Warren P. Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia: The Old World Setting of the Book of Mormon (Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Publishing, 2015); and George Potter and Richard Wellington, Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New, Documented Evidences that the Book of Mormon is a True History (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, Inc., 2003). For videos, see Lehi in Arabia, DVD, directed by Chad Aston (Brisbane, Australia: Aston Productions, 2015) and Journey of Faith, DVD, directed by Peter Johnson (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute of Religious Scholarship, 2006), https://journeyoffaithfilms.com/. [2] The three-part series for Faith Promoting Rumor was authored by the anonymous writer “RT”: RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia: A Historical Perspective, Part 1” (hereafter Part 1), Faith Promoting Rumor, Patheos.com, Sept. 14, 2015, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/faithpromotingrumor/2015/09/nahom-and-lehis-journey-through-arabia-a-historical-perspective/; also RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia: A Historical Perspective, Part 2,” Faith Promoting Rumor, Patheos.com, Oct. 6, 2015, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/faithpromotingrumor/2015/10/nahom-and-lehis-journey-through-arabia-a-historical-perspective-part-2/; and also RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia: A Historical Perspective, Part 3,” Faith Promoting Rumor, Patheos.com, Oct. 24, 2015; https://www.patheos.com/blogs/faithpromotingrumor/2015/10/nahom-and-lehis-journey-through-arabia-a-historical-perspective-part-3/. As for RT’s identity, the author information at Faith Promoting Rumor states that he is a lifelong member of the Church and a graduate of Harvard Divinity School. See “Guest Blogger: RT” at Patheos.com, Sept. 26, 2011; https://www.patheos.com/blogs/faithpromotingrumor/2011/09/guest-blogger-rt/. [3] RT, “Part 1.” [4] Lehi in Arabia, DVD, at 31:00 to 33:45. One of the early criticisms of Khor Kharfot as the place Bountiful is that the long wadi leading to it from the interior, Wadi Sayq, has large boulders on the ground that allegedly would make it impossible for Lehi’s group to travel through it to reach the seashore. Though you can see some boulders using Google Earth while looking along Wadi Sayq, feet on the ground there reveal that they are not a problem, according to Warren Aston. In Aston’s article “Identifying Our Best Candidate for Nephi’s Bountiful” at , he explains that he has made the journey and the boulders would not stop Lehi and his family: While it is true that Latter-day Saint tour groups wishing to see all Bountiful possibilities reach Kharfot by sea simply because it is easier than going by land, walking in to Kharfot is nevertheless quite possible. I have done so several times. Even after the 2600-plus monsoonal floods that have occurred since Lehi’s time, choke-points of accumulated boulders and abundant vegetation do not deter exploration by serious researchers any more than they would have turned away a prophet-led group long ago. The issue of boulders was also once raised as a barrier to making and launching a ship. A few minutes with the Lehi in Arabia DVD will show that this is simply not so. Aston also addressed this concern in “Identifying Our Best Candidate for Nephi’s Bountiful“: Wellington and Potter intimate that because Khor Kharfot is presently closed to the ocean by a sandbar, it cannot be Bountiful, although they acknowledge that Khor Rori is also closed. They then state that Kharfot, a place I know intimately, is “very narrow and the floor is strewn with huge boulders” (p. 42). Phillips also speaks about the Kharfot inlet as the smallest of the three sites, although he does not explain why that would be significant. Such claims make no sense to me. Kharfot’s inlet is not strewn with huge boulders; its width of a hundred or so feet is surely adequate to maneuver a ship, and its depth of about 30 feet is plenty for even a deep draft. Additionally, most of these assumptions fail if a raft-style craft were built rather than a conventional ship, a point that Phillips recognizes (p. 56). I also checked with Warren Aston directly. He suggests that the argument shows a lack of familiarity with the place, and further said (personal communication, 2015): The large boulders now there (2600 flash floods after the fact) at the junction of Wadi Sayq and Wadi Kharfot DO NOT block access to the coast…. But even today the boulders present no real barrier. One can climb through them and around them – I’ve done so many times, as have others…. Furthermore, locals bring large herds of camels and cows to the lagoon next to the beach through the junction all year around. (personal communication, 2016) His son, Chad, also told me this: I’ve walked a few miles inland through the wadi in both directions without any problem. Whilst this is different than a caravan of camels with children etc I believe it would far easier than walking on the plateau — shade, caves for shelter, wild game, fresh water and once you get closer to the coast — fruit. Lehi’s party would have been ecstatic just to get into the valley. There are certainly choke points which would have necessitated walking through water, or on the lower slopes, to get camels through but its hard to know how much more debris is there now after 2600 years. I think the flash floods would have been even larger back then, keeping the wadi floor even clearer. And, bottom line, locals do sections of it now (arguably the most blocked up sections) with cows, camels and goats so why couldn’t Lehi? (personal communication, 2016) The boulders of Wadi Sayq are not a problem. One issue only briefly treated in my work at The Interpreter is whether Nahom, linked to the name of the ancient Nihm tribe of Yemen, could have served as the name of a place. Here I wish to provide additional information, especially regarding the views of Dr. Christian Robin, a retired professor in France with expertise in Yemen’s history and tribes. RT states that tribal names did not get used as place names, and that Nephi’s calling Nahom a “place” is simply wrong and confused. Tribal names didn’t get used as place names, according to RT. While he must admit that the Nihm name today appears to describe both a region and a tribe, he argues that we can’t project this modern practice back into Lehi’s day. It’s not just the Nihm tribe whose name shows up on a map, very “placelike.” Bariq or Bareq, a governate that is sometimes referred to as a region or even a town, is also a tribe name. Ma-in is also a city and a tribe name. But these are modern manifestations, the thing RT says we can’t project back into antiquity, as if tribes with tribal lands and tribal places wouldn’t think of associating their names with those places back then. For this proposition, he appeals to personal correspondence from Christian Robin, a French professor and expert on Yemen, who says that ancient South Arabian inscriptions didn’t confuse toponyms with tribal names: Formal documents memorialized in stone will naturally refer to places with careful, more formal and precise language, just as our official and legal documents will often refer to the place Utah as the State of Utah. But in less formal contexts, ancient and modern, it would seem plausible that people could speak of a tribal land as a place with having to call it the Land of Nihm. To go from Robin’s point, if he is properly quoted and understood what he was answering, to RT’s conclusion that “it does not make sense to speak of Nihm as though it were a regular place name” strikes me as unfounded, especially in the context of what Nephi actually said, and in the context of what we know about Nihm. Nihm is a tribe and a place today, and we know that tribal name was significant in Lehi’s day. Nephi speaks of “the place called Nahom.” What exactly is the problem, apart from RT’s failure to yield one inch on anything? Nephi did not write that he came to Nahom, but to the place called Nahom. If he had spoken of the “land called Nahom,” would we not naturally understand that this could well have been known as “the land of Nahom” among the locals, just like the lands of the Himyar tribe were called “the land of Himyar”? Nephi is not reporting whether the locals saw the place Nahom as a village, mountain, region, or land, or a “regular place name” that didn’t need to be preceded by “land of” or “territory of.” He’s associating a local name that had significance to him (regardless of the precise way it was used by the locals in formal documents) with a place where a significant event occurred, and the place Nahom is the place (or land/country/region/village/mountain/burial site, etc.) where that occurred. Can we really say that “it doesn’t make sense”? Himyar was a tribe and a land — the land of Himyar, per ancient inscriptions. Today Nihm is a tribe and a place, and it was in earlier records. Further, as mentioned above, we could point to Bariq/Bareq as both a place and tribe, something that may not be a recent innovation which we cannot “retroject” into the past. Regarding Christian Robin’s views, we don’t have access to what Robin told him, but we do have access to what Robin has published, and there we learn of a potentially relevant example, though one, as I shall explain shortly, that I misunderstood. The relevant material comes from a chapter on Yemen. The source is Remy Audouin, Jean-Francois Berton, and Christian Robin, “Towns and Temples — The Emergence of South Arabian Civilization,” in Werner Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix (Innsbruck: Pinguin and Frankfurt am Main: Umschau Verlag, 1987), pp. 63-77. (The text alone is available archived from Yemenweb.com.) On page 63, Robin refers to the ancient name Ma’in, which, according to an ancient South Arabian inscription in Yemen, is a tribal name that also looks like it was treated as a place (though perhaps it’s not really that simple, as I’ll explain): But trade seems to have grown significantly only between the 8th and the 6th centuries B.C. The South Arabian inscriptions only rarely mention this trade, and even when they do, it is in parenthesis. An inscription (about 4th/3rd century B.C.) on a straight section of the city wall of Baraqish runs like this: Ammisadiq … and Sa’id …, leaders of caravans, and the Minean caravans who had set off in order to trade with them in Egypt, Syria and beyond the river…, at the time when ‘Athtar dhu-Qabd, Wadd and Nakrah protected them and their property and warned them of the attacks which Saba’ and Khawlan had planned against their persons, their property and their animals, when they were on their way between Ma’in and Rajma (= Nagran), and of the war which was raging between north and south…. [emphasis mine] Ma’in in this passage looks like it is a place, as is Rajma (= Najran on modern maps). It’s a place that has a physical relationship to another place, today the city of Najran. Travelers on an ancient inscription on a city wall mentioned traveling between Ma’in and Rajma. The authors speak of Ma’in several times as if it were a specific place in ancient times. It’s still a place, a city, today. Regarding Main/Ma’in as a place, see “Kingdom of Awsan” at Wikipedia and see Wikipedia‘s article on the Minaeans, which refers to the region that would become known as Ma’in (a place). Shortly after the above passage, Robin and his coauthors share something else (p. 63): This almost complete silence of the texts can be explained by the fact that merchants wielded power only in the small caravanning tribe of Ma’in, while the other states were dominated by a warlike aristocracy, who naturally were mainly concerned with their military prowess.[emphasis mine] Note that Ma’in is also a tribe. So at first glance, when I saw this, I thought I had found something interesting, but interpreting that writing to mean that Ma’in was known as a place may be my error as a newcomer to Yemeni tribes. I learned this when I checked directly with Dr. Christian Robin, who kindly answered my inquiry. He explained that, “In ‘between Main and Rajma,’ the first is attested only as tribe name ; the second is apparently a town name.” So apparently, though the translation of the inscription makes it sound like Ma’in is a place, a more nuanced understanding is that Ma’in is a tribe name only, so in speaking of going to or from Ma’in, what is meant is the place of the tribe Ma’in, not just Ma’in. A more nuanced translation, then, might speak of the place of the Ma’in tribe. My misreading of Christian Robin’s chapter led me to consider Ma’in as a place, but that’s the kind of mistake that a newcomer to Yemeni tribes can easily make, and, might I add, the kind of mistake that the ancient newcomer Nephi could have made as well. Or perhaps he just wasn’t interested in taking up a bigger space on the small plates for a more nuanced description of “the place of the tribe called Nahom” and instead made the newbie shortcut of calling it the “placed called Nahom.” This is not as sloppy as talking about going between Main and Rajma/Najran, but it is not completely satisfying for those who demand high precision in their ancient texts. Robin’s 1987 chapter that quotes the Baraqish wall inscription does not give a footnote with details of the inscription, but with a little searching I found it on an excellent resource for South Arabian inscriptions, the Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions (CSAI), part of DASI (Digital Archive for the Study of Pre-Islamic Arabian Inscriptions), a project directed by Alessandra Avanzini of the University of Pisa, AT CSAI, you can find the Baraqish wall inscription listed as “M 247 RES 3022; B-M 257.” It is in the Central Minaic dialect of Ancient South Arabian. You can see the inscription, its transliteration, and two translations. The translation from CSAI for verse 2 speaks of “the hostilities which Saba’ and Hwln brought against them and their goods and their camels, on the route between Ma’in and Rgmtm….” A translation by Walter Mueller speaks of the “Karawanenstrasse zwischen Ma’in und Rgmtm” (“the caravan trail between Ma’in and Rgmtm”). The transliteration includes the phrase “byn M’n w-Rgmtm” which I think means “going from/between Ma’in and Rgmtm” based on the meaning of byn. The link is to Joel A. A. Ajayi, A Biblical Theology of Gerassapience (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), p. 59. Then I noticed the “marker” button on that page which shows additional information for certain words, apparently due to markers on the inscription that identify what category a word belongs to. The marker information for Ma’in indicates that it is a tribe name, while Rgmtm is a toponym. That may be what Christian Robin meant. Would that marker have been conveyed in the spoken language? Would Nephi have recognized that NHM was meant to be a tribal name only if some spoke to him about coming to or from NHM?. Dr. Robin also added a valuable clarification regarding the alleged impossibility of tribal names also being place names: Normally the categories “territory” (country) and “population” (tribe) are distinguished. But, in Yemen (and perhaps in Eastern and Northern Arabia) on the borders of the desert, there are some instances of proper names used as a tribe name and also a town name (like Sirwah and Najran). [personal correspondence via Academia.edu, 2016, emphasis mine] So Nihm/Nahom/Nehem/NHM as an actual place name is not actually ruled out, though he went on to say that he felt it would be “unlikely” and said it is not attested as a pre-Islamic place name, just a tribal name. A tribe, of course, that is associated with a particular place. For a traveler to the place or the land of the tribe of Nihm/Nehem, referring to it as the place that was called Nahom seems undeserving of objection. Let’s give Nephi a break on this one. By the way, who was it that told Nephi that the name of the place was Nahom? I have naturally assumed that it was local Arabs, but Aston’s discussion of the significance ancient Jewish presence in Yemen raises the possibility that it was a Jewish group that Lehi’s family turned to for help with the proper burial of Ishmael. If so, they may have learned of the name not from South Arabian speakers, but perhaps from Hebrew speakers who may have already made the Nihm/Nahom connection to build upon the concepts of comfort and mourning linked to the Hebrew word Nahom, perhaps as part of their own involvement with death and burials in that distant land. That’s mere speculation, of course, and doesn’t affect the plausibility of a Hebrew speaker making the connection and finding a potential wordplay useful in the context of funerals. June 9, 2016 Update: If I was in error in thinking of Ma’in as the name of town as well as a tribe based on my literal reading of an interpreted passage from ancient South Arabian, it may not be the exclusive error of complete newbies to Yemen studies. In the same volume where I found Dr. Robin’s article with the ancient reference to Ma’in in what seemed to be a reference to a place name, I also found the next chapter, “Ancient South Arabian Sacred Buildings” by Jürgen Schmidt (in Werner Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix, 1987, pp. 78-98) to make the same “blunder”: A clear example for this can be found in the small, relatively well preserved building in the town Ma’in, which can, however, not be identified with absolute certainty as a temple… (p. 82, emphasis mine). So here is another professor in the same volume also speaking of Ma’in rather unmistakably as a town, making the tribal name Ma’in to also function as a place name. Dr. Schmidt is an archaeologist who has conducted field work in Yemen (Daum, Yemen: 3000 Years, p. 483). Further, a Yemen-born professor who taught at the University of Sanaa with extensive credentials in Yemen studies also seems to be unaware that Yemeni tribal names cannot also function as place names. In the volume just mentioned, Dr. Muhammad ‘Abduh Ghanim in “Yemeni Poetry from the Pre-Islamic Age to the Beginning of the Modern Era” (Daum, ed., Yemen: 3000 Years, pp. 158-166) writes about an early Yemeni poet who apparently wrote before the rise of Islam: His name was Malik ibn Harim al-Wadi’i al-Hamdani and the poem is about the town of Ma’in, the ancient capital of the Minaean kingdom. (Muhammad ‘Abduh Ghanim, “Yemeni Poetry” in Daum, ed., Yemen: 3000 Years, p. 160; emphasis mine) The pre-Islamic poem has this line: We shall protect the Jauf as long as Ma’in exists Down there in the valley, opposite ‘Arda! (Ghanim, p. 160) It’s hard not to see Ma’in as a toponym in that poem, with a location in a valley opposite ‘Arda. If ancient Ma’in could be a tribe and a town, is it really unreasonable to think that the could happen for Nihm/Nehem/Nahom? The ancient tribal name in South Arabian or related languages, like related words in Hebrew, was written with three letters, NHM. Those 3 sounds should be present. The vowels are less certain. But the name would not be pronounced the way the word looks to us in English, like “Neem.” It needs an H sound. On Christmas Day, 2015, I visited the Jamia Mosque in Hong Kong during an open house even there and made friends with a fascinating Muslim volunteer there who represented his religion with grace, enthusiasm and intelligence. I was deeply impressed, and then intrigued to learn that he was from Yemen, and had grown up in Sana’a, which I know is not far from the land of the Nihm tribe. I asked him if knew anything about the “Neem” tribe, and he quickly corrected my pronunciation. The way he spoke it, I can see why it would be written as “Nehem” on some maps of Arabia. To me, the H sounded harder than our H, though not as hard as the H in the Hebrew nacham. For my ears, I could also transliterate his pronunciation as Nehum, or Neh’m. Next time we meet, I’ll try to get a recording to share here. I suspect his pronunciation is fairly standard Arabic, but I think having it spoken by someone from that area is especially interesting. I’m curious to know if Nihm tribal members speak it the same way today. That may differ from the way it was spoken in 600 BC. What’s fascinating, though, is that we now know the tribe of that name was actually in the area in 600 B.C., so that we can even appropriately ask how their tribal name was spoken then, and how Nephi might have heard it. “In calling RT a minimalist, you cited his belief that Jeremiah and Ezekiel weren’t necessarily real people, and referred to evidence supporting the ancient origins of the book of Ezekiel. What about the Jeremiah?” A news story at Archaeology.org provides some relevant information on this issue. See Julia Sexton, “Book of Jeremiah Confirmed?,” Archaeology.org, July 23, 2007. Here is an excerpt: Scholars link biblical and Assyrian records. Austrian Assyriologist Michael Jursa recently discovered the financial record of a donation made a Babylonian chief official, Nebo-Sarsekim. The find may lend new credibility to the Book of Jeremiah, which cites Nebo-Sarsekim as a participant in the siege of Jerusalem in 587 B.C. The tablet is dated to 595 B.C., which was during the reign of the Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar II. Coming to the throne in 604 B.C., he marched to Egypt shortly thereafter, and initiated an epoch of fighting between the two nations. During the ongoing struggle, Jerusalem was captured in 597, and again in 587-6 B.C. It was at this second siege that Nebo-Sarsekim made his appearance. He ordered Nebo-Sarsekim to look after Jeremiah: “Take him, and look well to him, and do him no harm; but do unto him even as he shall say unto thee.” (Jeremiah 39.12) As the biblical story goes, the victorious Babylonian king departed the city with numerous Jewish captives. Desiring to spare the prophet Jeremiah, he ordered Nebo-Sarsekim to look after him: “Take him, and look well to him, and do him no harm; but do unto him even as he shall say unto thee.” (Jeremiah 39.12). Nebo-Sarsekim obeyed these orders by taking Jeremiah out of the Babylonian court of the prison, and ensuring he was escorted home to Jerusalem to live among his people. Aside from serving in the military, Nebo-Sarsekim evidently also fulfilled religious duties. Jursa was studying Babylonian tablets at the British Museum when he came across Nebo-Sarsekim’s name. According to Jursa, the tablet contained the record of a donation to a Babylonian temple, and his interpretation was later verified by curators at the British Museum. However, one can’t infer too much about Nebo-Sarsekim’s life from this transaction. Museum spokesperson Hannah Boulton states that it would have been quite common for a high-ranking official to contribute religious donations. It is not necessarily the case, therefore, that Nebo-Sarsekim was particularly pious or religious. The tablet may not reveal information about Nebo-Sarsekim’s lifestyle or personal beliefs, but it does lend credibility to the Book of Jeremiah. It is important because it shows that a biblical character did actually exist. Jursa states, “Finding something like this tablet, where we see a person mentioned in the Bible making an everyday payment to the temple in Babylon and quoting the exact date is quite extraordinary.” Boulton proposes an even deeper significance, suggesting that the finding may confer credibility to the rest of the Bible. “I think that it’s important in the sense that if [his name] is right, then…presumably a great deal of other info in [the Book of Jeremiah], but also generally in the Bible, is also correct.” The tablet is important because it shows that a biblical character did actually exist. That evidence, if accurate, doesn’t prove that Jeremiah was real, but supports the notion that the book of Jeremiah derives from ancient records from the time frame claimed rather than being a fraudulent document composed centuries later. The existence of an authentic ancient record behind the book supports the notion that Jeremiah was real, as do other references to Jeremiah in the scriptures. He’s also treated as real in Islamic sources. I don’t think anybody suspected he wasn’t even real until a few modern minimalists began tearing up biblical history. But that’s just my opinion. Dr. Kenneth A. Kitchen also offers a useful perspective on Jeremiah in On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), p. 381: The narrative parts of Jeremiah contain many allusions to well-attested contemporary history, and various Hebrew seals and bullae mention people who are almost certainly (in some cases, certainly) characters found also in Jeremiah [see chapter 2 of Kitchen]. To date much (or any) of Jeremiah to distinctly late periods (e.g., fifth to third centuries) would seem impractical, given the lack of detailed, separate (nonbiblical) knowledge of preexilic history, dating, and people in (say) the fourth/third century, which would prevent anyone concocting then a “Jeremiah” book as we have it now. In a response to my articles, RT claims that I misread his statement on Jeremiah and Ezekiel, for he actually meant it wasn’t clear whether their books were historical, not the characters themselves. However, the evidence I present in return is addressed to the historicity of the books, not the prophets themselves. Here is what I wrote in Part 1 of the “Technicolor Dream Map.” Judge for yourself who is misreading whom: RT seems to among these so-called “minimalists” (for minimalizing the historical value of the biblical record) given the criteria he applies in labeling events as fictional and especially given that he does not seem to accept the reality of Jeremiah and Ezekiel as real prophets who existed before the Exile. In response to an argument from biblical scholar Richard Elliot Friedman citing passages from Jeremiah and Ezekiel to support for an early date for the presumed source used in much of Exodus, RT replied: “This is begging the question. We do not in fact have evidence that Jeremiah and Ezekiel existed before the exile.” This is surprising, since according to well-known Bible scholar Richard Elliot Friedman, proponents of the “Documentary Hypothesis” (discussed in Section 4) have not argued that Ezekiel and Jeremiah were written much later by someone else or that the Exodus-related material was patched into their books by late redactors, and James K. Hoffmeier notes that “the chronological data interspersed throughout the book of Ezekiel makes it one of the most securely dated books in the Hebrew canon.” I see RT’s view as a rather radical position not shared by a majority of scholars. But given that perspective, it will not be surprising that numerous aspects of the Book of Mormon would be found guilty of being fiction, especially those that lack granular detail consistent with his expectations or those that draw upon biblical themes. In addition to the resources listed in the Interpreter articles, there are other useful sources on Arabia and related issues include. One recent article of note is an interview with William Glanzman, professor of anthropology at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Canada, by James Wiener in “The Kingdoms of Ancient Arabia,” at Ancient History, Etc. (etc.ancient.edu), Aug. 2014; https://etc.ancient.eu/2014/08/08/the-wealthy-kingdoms-of-ancient-arabia/. This has a good discussion of the multiple ancient kingdoms in Yemen and points to the many things still not known, awaiting further research. Some basic reading on the evidence from Arabia includes: Related video content includes George Potter and Richard Wellington giving a 2003 presentation on their work, “Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New Evidences” (part 1). Also see Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6. There are points one can take issue with, but the scope of their on-site work demands attention and serious consideration, especially for the candidate for the River Laman and the Valley Lemuel.Overview of the Publications at the Interpreter

The Potential Role of Maps

The “Exodus Never Happened” Theory

Conclusion To Date

Citations

Further Issues (Beyond My Content at The Interpreter)

Boulders Blocking Wadi Sayq?

Can a Tribal Name Be a Place? Misunderstanding Dr. Christian Robin (My Error!)

[S. Kent Brown states that] there were actually two closely interrelated usages of the root NHM as an appellative in ancient south Arabian culture, one used to denominate the tribal group itself (the people Nihm) and another to refer to its territory (the Nihm region), a conclusion that finds support in the modern use of the term Nihm to designate a tribe as well as a geographical district in present day Yemen. However, it is doubtful that this later use of tribal names to refer to geographical entities can be retrojected onto much earlier periods and careful examination of South Arabian inscriptions indicates that the names of tribes were essentially social-political in orientation. Christian Robin, one of the world’s foremost experts on the tribal history of ancient South Arabia, explains that the tribal names “are not toponyms nor ancestor names. But they were used as eponyms when the genealogies were elaborated in late Antiquity and early Islam…. The tribes in the south are strictly connected with a territory. But, in general, there is no confusion. The inscriptions distinguish always between Himyar [a south Arabian tribe] and ‘the Land of Himyar’.” Accordingly, within an ancient south Arabian context, it does not make sense to speak of Nihm as though it were a regular place name.

Why Do You Think the Name Nihm Would Sound Like Nahom to Nephi? Isn’t It Pronounced “Neem”?

Evidence for Jeremiah?

Wait, You Misread RT Since He Wasn’t Talking About Jeremiah and Ezekiel Being Non-Historical, Just Their Books!

Further Reading Materials